HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

From December 1941 to February 1948, the U.S. government orchestrated and financed the mass abduction and forcible deportation of 2,264 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry from 13 Latin American countries to be used as hostages in exchange for Americans held by Japan. Over 800 Japanese Latin Americans were included in two prisoner of war exchanges between the U.S. and Japan. The remaining Japanese Latin Americans were imprisoned without due process of law in U.S. Department of Justice internment camps until after the end of the war.

Stripped of their passports en route to the U.S. and declared “illegal aliens”, most of the incarcerated Japanese Latin Americans were forced to leave the U.S. after their release from camp. However, since many were barred from returning to their home countries, more than 900 Japanese Latin Americans were deported to war devastated Japan. Over 350 Japanese Latin Americans remained in the U.S. and fought deportation in the courts. Eventually, about 100 were able to return to Latin America. It was not until 1952 that those who stayed were allowed to begin the process of becoming U.S. permanent residents. Many later became U.S. citizens.

Japanese Latin Americans were subjected to gross violations of civil and human rights by the U.S. government during WWII. These violations were not justified by a security threat to Allied interests. Rather, it was the outcome of historical racism, anti-foreign prejudice, economic competition, and political opportunism. The U.S. government has yet to properly acknowledge this wrongdoing against the Japanese Latin Americans.

CIVIL LIBERTIES ACT OF 1988

Like Japanese Americans, Japanese Latin Americans have played an integral part in the struggle for acknowledgement and redress by the U.S. government for its unjust treatment of people of Japanese ancestry in the U.S. As a result, Congress enacted the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 to make the U.S. credible in the eyes of the world on human rights issues. To accomplish this, the Act provided for an official apology and token reparations of $20,000 to eligible individuals of Japanese ancestry. It also created a fund to educate the public about the internment to prevent the recurrence of similar events.

However, under this Act, individuals were eligible for reparations only if they were U.S. citizens or permanent resident aliens at the time of internment. Since the U.S. maintains the fabrication that Japanese Latin Americans were “illegal aliens”, they were excluded from the Act. Only 189 Japanese Latin Americans were given redress under the Act because they were either born in camp or granted retroactive permanent residency.

LAWSUIT

In 1996, a class action lawsuit, Mochizuki v. U.S.A., was filed against the U.S. government on behalf of all Japanese Latin American internees who were denied redress under the Act. A settlement agreement was reached in 1998 that provided for an official apology and the possibility of $5,000 in compensaútion payments to eligible Japanese Latin Americans. This settlement was controversial because it did not fully acknowledge the severity of their human rights violations. It did, however, contain essential provisions that allowed internees to opt-out of the settlement and continue litigation, and also allowed internees to pursue redress equity through legislative efforts.

Under the Mochizuki settlement, the token reparations, which were only one quarter of what Japanese Americans received, was not guaranteed. Despite assurances that all Japanese Latin Americans would receive redress payments, only 145 were paid before the funds were depleted. It was only after community effort and pressure for additional funding that supplemental appropriations were given by Congress to allow the remaining Mochizuki claimants to be paid. In addition, less than two months notification was allowed for Japanese Latin Americans to apply and the government refused to release applicant information to internee attorneys to ensure proper processing.

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES

The fight for justice continues today for Japanese Latin Americans in litúigation and in legislation. Campaign

for Justice is currently seeking comprehensive legislation that would serve to fulfill the education and compensation mandate of the Civil Liberties Act and to resolve the unfinished redress business.

We urge our communities to support these efforts to acknowledge and redress the fundamental injustices suffered by Japanese Latin American during WWII. We cannot allow this chapter of American history to close until our government makes proper amends for its actions.

Justice for the Forgotten Internees

By Xavier Becerra and Dan Lungren Monday, February 19, 2007;

washingtonpost

Art Shibayama is an American who served in the Army during the Korean War. Like many veterans, Cpl. Shibayama was not born in the United States. He was born in Lima, Peru, to Japanese Peruvian parents. Until 1942, Shibayama, his two brothers and three sisters lived comfortably with their parents and grandparents, all of whom had thriving businesses. However, after America entered World War II, his family was forcibly removed from Peru, transported to the United States and held in a government-run internment camp in Crystal City, Tex.

Like many Japanese American families, Shibayama's family lost everything they owned. But the greater injustice occurred when his grandparents were sent to Japan in exchange for American prisoners of war. Their family never saw them again.

Shibayama and his family were among the estimated 2,300 people of Japanese descent from 13 Latin American countries who were taken from their homes and forcibly transported to the Crystal City camp during World War II. The U.S. government orchestrated and financed the deportation of Japanese Latin Americans for use in prisoner-of-war exchanges with Japan. Eight hundred people were sent across the Pacific, while the remaining Japanese Latin Americans were held in camps without due process until after the war ended.

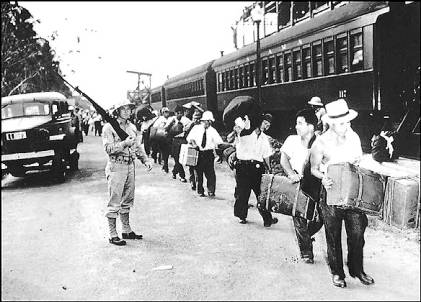

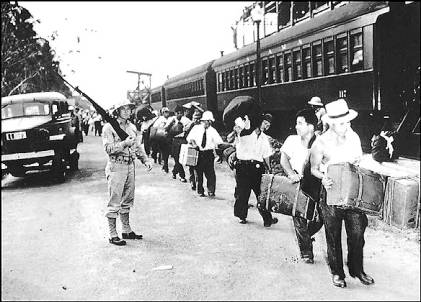

Japanese Latin Americans en route to U.S. internment camps during World War II.

Further study of the events surrounding the deportation and incarceration of Japanese Latin Americans is merited and necessary. While most Americans are aware of the internment of Japanese Americans, few know about U.S. government activities in other countries that were fueled by prejudice against people of Japanese ancestry.

That is why we have introduced H.R. 662, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Latin Americans of Japanese Descent Act. We should review U.S. military and State Department directives requiring the relocation, detention and deportation of Japanese Latin Americans to Axis countries. Then we should recommend appropriate remedies. It is the right thing to do to affirm our commitment to democracy and the rule of law.

This year marks the 26th anniversary of the formation of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, whose findings led to the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. It provided an official apology and financial redress to most of the Japanese Americans who were subjected to wrongdoing and confined in camps during World War II. Those loyal Americans were vindicated by the fact that not a single documented case of sabotage or espionage was committed by a Japanese American during that time. This act was the culmination of a half-century of struggle to bring justice to those who were denied it. But work to rectify and close this regrettable chapter in our nation's history remains unfinished.

U.S. involvement in the expulsion and internment of people of Japanese descent who lived in various Latin American countries is thoroughly recorded in government files. These civilians were robbed of their freedom -- their civil and human rights thrown by the wayside -- as they were kidnapped from nations not directly involved in World War II. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians acknowledged these federal actions in detaining and interning civilians of enemy or foreign nationality, particularly those of Japanese ancestry, but the commission failed to fully examine and report on the historical documents that exist in distant archives.

Today, the Day of Remembrance, marks the anniversary of the 1942 signing of Executive Order 9066 -- the document that made it possible to intern thousands of Japanese Americans, German Americans, Italian Americans and Japanese Latin Americans during World War II. Though it is important that we remember what took place, it is more critical that we act, for justice delayed is justice denied. And for the dwindling number of surviving internees who became Americans, such as Cpl. Art Shibayama, justice has been delayed far too long. They deserve our attention, our respect and the official recognition of a country that is willing to heal and to make amends.

Xavier Becerra, a Democrat, and Dan Lungren, a Republican, are U.S. representatives from California.