Home | Who We Are | Past Events | Open Forum | Campaign for Justice | Contact Info | Membership | Links | Search |

||||

Home | Who We Are | Past Events | Open Forum | Campaign for Justice | Contact Info | Membership | Links | Search |

||||

More Stories

|

||

| The publishing of "“NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle for Japanese American Redress and Reparations” has created a demand for more stories on the individuals that shaped the Movement. The following is the first of new stories on those that fought for our rights and continue to do so. | ||

|

||

The General Has His Rambunctious Moments |

||

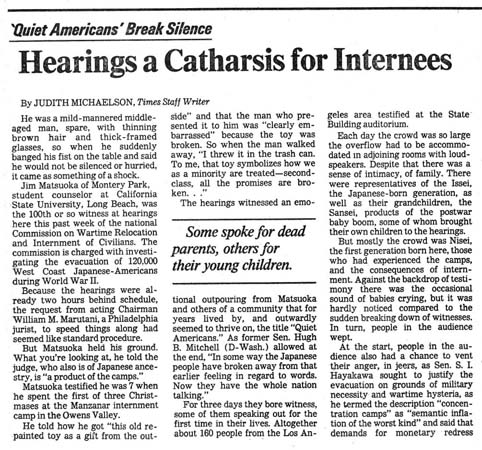

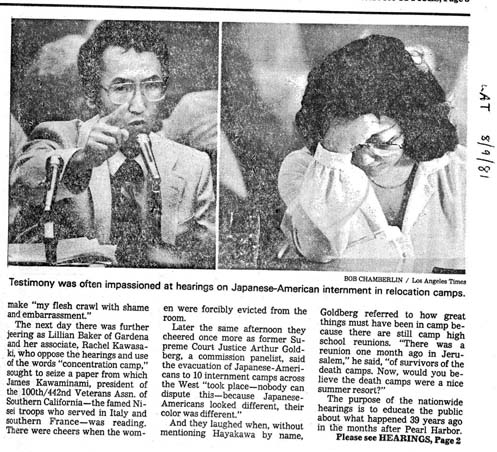

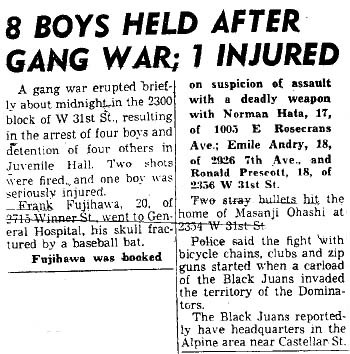

Los Angeles, 1981—It’s the first of the community-wide hearings scheduled by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. The hearing room is packed, the commissioners are already two hours behind schedule, and they are trying to speed up the testimonies. “For the sake of brevity, submit your written testimonies in lieu of testifying,” comes the word from the Commission. Up next is an older Japanese American man, looking very much like many of the Nisei men and women that testified earlier in the day. This time, however, as the commissioners ask the group to hurry things up, what comes next is unexpected. THE OLD MAN SLAMS HIS FIST TO THE TABLE. The sound echoes against all four corners of the auditorium, and brings the hearing to a halt. “I will not be hurried! I’ve waited forty years for this!” The attendees break out in applause. William Marutani, the acting chairperson of the Commission on this day, succumbs to the sentiment in the audience, “Take as much time as you need.” This incident forever changes the tenor of the testimonies. The gentleman is Jim “The General” Matsuoka, who then speaks about how he received an old, repainted toy as a gift from the outside during one Manzanar Christmas. “The man who present it was clearly embarrassed because the toy was broken. When the man walked away, I threw it in the trash can. To me, that toy symbolizes how we as a minority are treated: Second class. All the promises are broken.” Up until the hearings, Jim was organizing older Nisei to testify before the commission. In more recent years, he played a role in exposing the international criminal past of the then newly hired director of the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center, leading to that director’s ouster. It was 30 years earlier that Jim acquired the nickname ‘The General’. Back then, he helped lead one of the most notorious street gangs in the Japanese American community. THE GANGS OF LOS ANGELES Before Japanese American redress, before the Asian American movement, and before the civil rights movement gained momentum, there were street gangs in the community challenging the norms of society in the only way they knew how. “They knew they were being bullshitted. They knew that somehow society was pulling shit on them. …But they didn’t know how it was being done. There was no Movement. There was no Malcolm X. There wasn’t even a Martin Luther King at the time. Segregation, in 1953, was an accepted way of life,” said Matsuoka about his former gang, the Black Juans. After Manzanar, the Matsuoka family moved to J-Flats in the Virgil area, near Clinton, where a pocket of Japanese Americans lived. The Hollywood gakuen and judo dojo are still there. There were Mexican gangs in East L.A. like First Flats, Fourth Flats, and Tortilla Flats. The ‘flats’ referred to the apartment structures. “Back around 1950, I went to Belmont High School and didn’t know a soul. One day, a car pulls up and I hear ‘Hey, cuz.’ My cousin, Donji (Donald) Morinaga, was the originator of the Black Juans. He asked me if I wanted to go to a dance. [Later,] I meet some people on the Westside and they say, ‘I heard you guys are having a fight.’ My cousin says, ‘Nothing is going to happen. And don’t worry because I’ve got the backing of these two other groups. We are just going to parties and dances. And if somebody should jump us, we’ll have each other for protection.’” The Black Juans left their mark way into the early 1960s. There were junior clubs that wanted to be affiliated with them, such as the Baby Black Juans. At some point, the seniors all got drafted, and Jim was the only senior left. THE GENERAL “We used to go to Linda Lea Theater on Main and Second Street in Little Tokyo. Those movies would bust us up. There was a detective series with a character named Lieutenant Matsuoka. So my friends would burst out in laughter and call me Lieutenant Matsuoka. My cousin says, ‘That’s not good enough. Let’s promote him.’ So I started being called General. My parents didn’t really know what was going on until somebody got killed. I had older sisters. They allowed us to survive after the war by getting jobs as nurses’ aides. The killing dragged us into the picture. My mother said, “It gives me a headache just to read about it. What the hell are you doing?” I had been fighting the draft but now I thought it was time to get out of Dodge. I was being blamed for all kinds of stuff. So I allowed them to draft me. I was 23. THE ASIAN AMERICAN MOVEMENT Some years went by after the draft before Jim entered a time in his life that would forever change him. It all started from a visit to a local campus: When Asian American activists in Los Angeles first got together in 1969-70, we called ourselves Oriental Concern. I ran into a guy named Mo Nishida. He was a Constituent (the arch rival group to the Black Juans) from the Westside (laughs). It kind of took off from there. I joined Los Angeles Pioneer Project, a group that wanted to make things better for the aging Issei. I got involved in Asian Americans for Political Action (AAPA) that opposed the war in Vietnam in 1969-70, the Anti-Eviction Task Force around 1973, and Little Tokyo People’s Rights Organization (LTPRO) around 1976. I also joined Manzanar Pilgrimage Committee. I was a member of OSAAO – Organization of Southland Asian American Organizations, an umbrella group. I represented Cal State LA. It was OSAAO that sponsored the first Manzanar Pilgrimage with Victor Shibata, Mo Nishida, and Warren Furutani, who was the chair of OSAAO. Alan Nishio and Linda (Miya) Iwasaki were the delegates from USC. We had delegates from UCLA, Occidental, and Cal State Long Beach. THE REDRESS MOVEMENT In the late 1970s, many of the volunteers at LTPRO became active in LACCRR, the Los Angeles Community Coalition on Redress and Reparations. In 1981, at Cal State LA, the members of LACCRR laid the groundwork for NCRR, the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations. Jim was one of the founding members of both LACCRR and NCRR: So Bert Nakano and I only had six-to-eight testifiers for the Commission Hearings. We were looking at a disaster. This was two or three weeks before the hearings. At one NCRR meeting, I had a solution, “Everybody in this room will have to testify, including myself.” That was about 12 of us. But in the last week, about 15-16 people came flooding in. We were on the phone! All of a sudden, we had about 35- 40 testifiers and the JACL (Japanese American Citizens League) had about the same.” “JIM, DO SOMETHING!” Jim recounts what led up to one of the more memorable incidents at the Los Angeles commission hearings: Lillian Nakano was sitting in the front row and yelling, ‘Jim, do something.’ I said to myself, ‘What the hell.’ So I pounded the table and said into the microphone, ‘You are not going to keep me quiet.’ It was going to screw all my work so I go into a tirade. You can see this video sequence with me pounding on the table on YouTube. I was pissed. I stormed out of there. That lady from the LA Times came up to me afterwards and said, ‘Did you stage all of this?’ I looked at her with anger. I had to bite my tongue. I was on the front page of that sucker. After that particular session, Judge Marutani changed his tone and let everyone talk for as long as they wanted. That evening, it was Bill Shinkai who said, ‘We are finally getting out of the camps.’ Later, we had a Senate hearing at the West Los Angeles Veterans Administration. NCRR people said to me, ‘Jim, we want to win over the senators. And we don’t want you to have an outburst’ (laughs). I’m really not prone to fits of anger unless provoked. The opposition was there at the hearings. They were against redress. Rachel Kawasaki was a White woman married to a J-A and she was raging. Senator Stephens from Alaska got so turned off that he wouldn’t listen to them anymore. He was talking to his aide. Another vocal opposition was Lillian Baker. I got her goat once. We were in a Gardena meeting and she was livid. She had been a journalist for the Gardena Valley News. She was shaking and said, ‘My husband went to the Pacific and never came back.’ I got up and said, ‘Well, if I was married to you, I wouldn’t come back either’ (laughs). Everybody cracked up. That was the best retort of my life (laughs). Lillian Baker got so crazy that she actually helped NCRR a lot. NCRR TODAY Although decades have passed since the commission hearings, Jim remains active in NCRR, now known as Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress. “We went into other civil rights issues with the Muslim community. There is also a controversy over the comfort women statue in Glendale (NCRR supports the comfort women). We are against the NDAA, the National Defense Authorization Act – a spinoff of the Patriots Act. We oppose the government’s ability to hold you indefinitely. It negates everything we stand for. In response, I went to a mosque in Ontario with NCRR. We explained how the anti-Japanese camps are related to today’s anti-Islamic sentiment. As we were leaving the Ontario mosque, there was a big ass American flag across the street. Normally, it doesn’t bother me. But this was a slap in the face of those Muslims. These racist bastards are doing the same ol’ thing again.” THE JACCC INCIDENT For many years now, NCRR has been holding its meetings at the Japanese American Community and Cultural Center (JACCC) in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. The JACCC has been a hub for activities in the community. In 2012, something happened that grabbed the attention of NCRR: “We couldn’t help but notice that some of our friends and colleagues that had been working at the JACCC were abruptly quitting. The reason cited was the new JACCC president and chief executive officer, Gregory Willis, who came on board in January of 2012. A few of the current and former staff of the JACCC approached us about their displeasure with how things were being run under the new CEO. The JACCC board of directors are saying it hired Willis after an extensive national search and for his impressive range of professional experience in Japanese, American and international business settings. They even hired an executive search firm, Johnston & Company of Culver City, to vet out the new CEO. So I’m having a casual conversation about the situation with my son, James. At the time, he was working with some of the folks there. ‘By the way, he’s a fugitive from justice, and the French government wants him for misuse of corporate assets,’ says James. After I picked my jaw up off the floor, I snap into consciousness, ‘What are you talking about?’ ‘Oh yeah, you can Google it,’ says James. So, he’s showing me the information after typing in ‘Gregory Willis’ on his laptop. Sure enough, there are the press accounts, with photos of the same Gregory Willis, in black and white. “WE CANNOT NOT DO SOMETHING” At the time, James didn’t want to be linked as the source of this revelation. After all, he was still working with the people there. “But we cannot not do something,” says Jim. “We both knew that. So, that evening, I made some calls to the other NCRR board members. The next morning, we met, and soon thereafter, NCRR met with the JACCC board of directors to present our findings. We had been meeting with the board to voice our concerns about what was happening to the JACCC, but this piece of information changed everything.” The revelations about the CEO hit the papers—not just the Japanese American press, but the mainstream press as well. Meanwhile, NCRR felt that not enough information was coming from the JACCC board. So Jim sent an open letter to The Rafu Shimpo to summarize NCRR’s concerns: REFLECTING BACK At the first Manzanar Pilgrimage, I spoke for the Organization of Southland Asian American Organizations. I said, ‘People ask me how many people are buried at this cemetery. A whole generation has died here. People are afraid to speak, to stand up for what is right.’ Some JACLers got mad at me for that. But that’s how I feel. My dad may not have amounted to what he may have dreamed, but we didn’t come to America to pull rickshaws. Biographical background: Jim Matsuoka was born in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. He attended 9th Street School just before being incarcerated in the camp at Manzanar. Upon the family’s return to Los Angeles, they started in a trailer park with Terminal Islanders before moving to the Westside (Crenshaw) area and then to J Flats (East Hollywood area). He graduated from Belmont High School. Jim was involved in an early Japanese American “social club” or gang called the Black Juans in the 1950s. He was later drafted into two years of active duty at Fort Huachuca in Arizona. Upon his return, he attended LACC and then Cal State LA. He was one of the originators of the Asian American Studies Group at CSULA, and in 1969, he wrote its first constitution. Jim worked for the Educational Opportunity Program at CSULB as the Associate Director of Retention Services. Jim Matsuoka is a community activist, and has been a member of the Manzanar Committee at its inception, a member of the Los Angeles Pioneer Project and the National Coalition for Redress and Reparations (later renamed Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress). Jim lives in West Covina, California. For more background information on Jim Matsuoka, see his Densho Oral History interview and interviewed with Kasumi Yoshida, Legacy of Japanese American Activism Conference http://jalegacy2011.wordpress.com/narrative-interview-essays/jim-matsuoka/. |

||

| More images | ||

|

] |  |

| Los Angeles Times, 8/9/81, Coverage of the hearings | ||

|

|

|

| Asian Gangs- Black Juans | Writer: Katie Ling Nakano | |