Home | Who We Are | Past Events | Open Forum | Campaign for Justice | Contact Info | Membership | Links | Search |

||||

Home | Who We Are | Past Events | Open Forum | Campaign for Justice | Contact Info | Membership | Links | Search |

||||

NCRR Fighting Spirit Award

During World War ll, the United States government kidnapped over 2,200 Japanese Latin men, women and children to be used in a hostage exchange program with Japan. Shibayama and his family, natives of Lima, Peru, were forcibly removed from Peru in 1944 and imprisoned at Crystal City,Texas for two and a half years. Once an affluent businessman, Shibayama’s father struggled to support his family of eight children through a variety of odd jobs after they were released from camp. The family traveled from Texas to the Seabrook Farm in New Jersey and then to Chicago to find suitable work.The elder Shibayama passed away in 1976. By 1993, most eligible Japanese Americans had been issued an apology and reparations from the government through the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. However, many Japanese Latin Americans were being denied the $20,000 because the legislation provided compensation for only U.S. citizens and permanent residents. The Japanese Latin Americans had their passports taken from them before their imprisonment in the U.S. and now were being denied redress for their illegal alien status during the War.

In 1996, the CFJ and lawyers helped a small group of Japanese Latin Americans file a lawsuit against the U.S. government to win reparations. The offer of an out-of-court settlement in 1998 was accepted even though only $5,000 was provided for each surviving former internee. Shibayama and his brothers, Kenichi Javier Shibayama and Takeshi Jorge Shibayama, both of Chicago, refused the settlement along with 14 other former internees.These “opt-outers” believed the settlement was not sufficient given the larger amount given to Japanese Americans. The Shibayama brothers’case remains pending at this time. NCRR Special recognition

Each of the following redress litigants had applied for but was denied reparations in the early 1990’s because of the Department of Justice’s strict interpretation of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The eight worked closely with several lawyers who volunteered their time to bring justice to those denied justice. Although only one of the litigants has thus far successfully won redress through the courts, NCRR is hopeful that the others, and the categories of people that they represent, will ultimately obtain redress through the Campaign for Justice’s push for legislation in Congress. 1. Carol Higashi was born February 6, 1945 less than three weeks after the eligibility cutoff birth date of January 20, 1945. Ironically, because her father couldn’t earn a living outside of camp Carol’s family returned to Tule Lake after her birth and remained at Tule Lake until July 21,1945. 2. Wendy Hirota, whose father was subjected to an individual exclusion order and could not return to the West Coast, was born in Colorado after the January 20th cutoff date. 3. Kay Kato, a lawful resident of San Francisco on a renewable merchant visa, was interned at Rohwer, Arkansas with his wife and son. Despite his imprisonment with other Japanese Americans, he was denied redress because of his lack of permanent residency status. 4. Robert Murakami was born one month after his father’s individual exclusion order was lifted in July 1945. 5. The four members of the Ogura Family were kidnapped from their home in Peru and brought to Crystal City, Texas by the U.S. government. Unable to return to Peru they settled in Japan where they still live. 6. Henry Shima was forcibly removed from Peru by the U.S. government and held at Crystal City, Texas. Like other Japanese Latin Americans he was to be used in exchanges for American citizens captured by Japan. 7. Carole Song was born in New Jersey after the January 20,1945 cutoff date. She received a favorable ruling from the court in Song v US because her parents, who worked at Seabrook Farms, had not received adequate notice that they could return to their West Coast home. 8. Jane Yano was born in the Department of Justice Internment Camp at Crystal City, Texas in 1947. Although an internee, she was born after the June 30, 1946 eligibility date established by the Civil Liberties Act (Crystal City Internment Camp remained open until 1948). Senior Advocate Janet Saisho worked tirelessly on behalf of redress applicants who came to the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center for help. She corresponded with the Office of Redress Administration, traveled to Washington, DC and lobbied California’s senators on behalf of Mr. Kay Kato and others who were denied redress. JACL PSWD: COMMUNITY ACHIEVEMENT AWARD

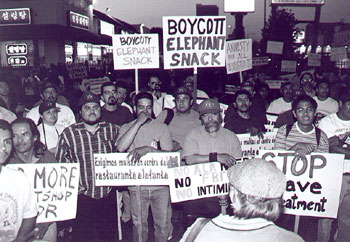

In 1997, KIWA helped win over $2 million for workers from retailers and manufacturers connected with the El Monte”slave shop” operators. KIWA organized 55 Latino garment workers and was a part of the legal team that eventually won this landmark case. In collaboration with other progressive organizations, KIWA fought to maintain the state’s affirmative action programs, raise the minimum wage, lower bus rates for the poor, save hundreds of union jobs at two local hotels and win dignity and respect for workers locally and internationally. KIWA initiated the Koreatown Restaurant Workers Justice Campaign. Immigrant restaurant workers in Koreatown labored up to 72 hours per week for as low as $2.20 an hour and faced brutal abuse from their employers in the form of unfair firings and physical abuse. The problems were exacerbated by the fact that the workers were not provided workers compensation and healthcare benefits even though they often work in unsafe work environments. KIWA organized Korean and Latino restaurant workers to demand an industry-wide reform that included raising sub-minimum wages, raising substandard working conditions, gaining a voice for workers in the industry and in the community through collective activism. |